It's kind of pleasing to find that the lady is a mystery. Most of what little I know of her is from the diary, and since she says almost nothing of herself there, I have to infer that little.

This diary entry Boswell-like reports dinner-table conversation. As you'll see, it's excellent story telling. She was 21 years old and two years married when she wrote it. I've included some context below the entry.

February 28th, 1766. Lord Dunmore, Mr. Hume, the author [i.e., David Hume], and Mr. Cambridge [a poet] dined here. Mr Hume was Secretary to Lord Hertford's Embassy at Paris, when he was received with an uncommon openness, on account of his reputation as an author, and the esteem the English were in then since the peace. His company was universally courted, and he was the first person that got admission to the Scotch College to see seven volumes of King James the Second's writing there, which he had left to that Society at his death, together with all his correspondents' letters from England, and his heart to be deposited there. The books were all wrote in his own hand and contained an account of most part of his life. The papers he was not permitted to see, Father Gordon alleging that they contained letters from many people in England to the time of his death, who never had been suspected and might suffer by their names being known.

It appears from these books that soon after the triple alliance in 1667, Charles II. concluded a Treaty with Louis XIV. with a view to establish the Roman Catholic religion in England and stipulating for the conquest and subsequent division of the Dutch territory. The only difficulty after this Treaty was which object should first take place. The Duchess of Portsmouth upon this came to England and gaining her point war broke out soon after. The King says in these memoirs that brother, Charles II. was so bigoted that in the little Council where the Treaty was settled, he cryed for joy at the prospect of bringing in the Roman Catholic religion in England. It was signed by the Lord Arundel of Wardour at Paris on the part of the King. There were likewise several sheets of advice to his son. In them he takes his resolution for granted and advises him of all things to beware of women; he says that very far in life he was seduced by the allurement of the sex and repeats to him again and again to beware of such cattle. He desires him to make it his first and immediate object to get that pernicious Act, the habeas corpus, repealed and that for the good at the subject. For if that was done the prerogative would be strengthened, standing armies rendered unnecessary, and Government easier executed and less burthensome. He attributed most of his difficulties to his father-in-law, Lord Clarendon, not taking advantage enough of the times to gain more points in favour of prerogative.

Mr. Hume also said the Young Pretender was in England in the year 1753 that he walked all about London and went into Lady Primrose's, when she had a good deal of company. She was so confounded that she had scarce presence of mind to recover herself enough to call him by the fictitious name he had given her servant. When he went away her servant told her that he was prodigious like the Prince's picture that hung over the chimney. He afterwards abjured the Roman Catholic Religion in a church in the Strand, under the name even of Charles Stuart. He was at different times greatly connected with the first people of reputation in Europe, among others with M. Montesquieu. M. Helvetius did all his business for him from about the year 1750 to 1753, and was intrusted with all his secrets, and told Mr. Hume it was surprising even then how many people kept up correspondence with him from England. These people took great pains in removing prejudices from his character, but it at last ended in his having no religion at all, and by degrees he was given up by them and almost everybody who knew anything of his personal character, on account of the meanness and iniquity of it in every respect. He appears to have but one good quality or rather resolution, which was never to marry, though he has been often pressed to it, particularly by the French Court. He always said he had met with too many misfortunes to wish to contribute to anybody's suffering the like, and was so particular on the subject that he had a daughter by Mrs. Walkinshaw, which he took particular care should be christened at Liége, and then publicly declared to be his natural daughter. The French however made a point of getting her from him, though he parted with her with great regret and difficulty. They have taken care of her, and educated her in a convent in France.

Here's some context on people and events Sophie mentions in this entry:

Lord Dunmore was a Scottish peer who was later to be Governor of New York and then, just before the American Revolution, of Virginia. He fought in the war and is noted for freeing slaves -- the first mass emancipation in North America (he offered freedom to enslaved Africans who joined his Army). He was in his early 30's when the dinner took place. This portrait (from the Tate Gallery) by Joshua Reynolds was made the year before.

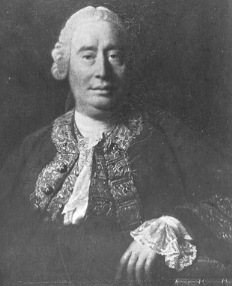

Lord Dunmore was a Scottish peer who was later to be Governor of New York and then, just before the American Revolution, of Virginia. He fought in the war and is noted for freeing slaves -- the first mass emancipation in North America (he offered freedom to enslaved Africans who joined his Army). He was in his early 30's when the dinner took place. This portrait (from the Tate Gallery) by Joshua Reynolds was made the year before. I'm sure David Hume is known to all. He was highly regarded as a historian during his own time, and a philosopher in succeeding ones.

The reference to Hume as secretary to Lord Hertford's Embassy at Paris concerns the Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years' War In 1763 Lord Hertford represented Britain in Paris with Hume as his secretary and when Hertford left in 1765 Hume stayed on as Chargé d'affaires.

One source confirms what Sophie says about Hume's reception by the French: "Though 'entirely unmoved by the raptures of Paris,' Hume moved in the highest of circles. 'In the gay and fashionable circles of Paris his fame, station, and agreeable bearing, secured him so hearty a welcome that ladies and princes, wits and philosophers, vied in their attentions.'"

One source confirms what Sophie says about Hume's reception by the French: "Though 'entirely unmoved by the raptures of Paris,' Hume moved in the highest of circles. 'In the gay and fashionable circles of Paris his fame, station, and agreeable bearing, secured him so hearty a welcome that ladies and princes, wits and philosophers, vied in their attentions.'" In 1766, at the time Sophie wrote this diary entry, Hume was an Under-Secretary of State in the Home Office under Lord Hertford's brother who was Secretary of State.

I haven't been able to identify the poet Mr. Cambridge.

The Triple Alliance of England, Sweden, and the Dutch republic aimed to stop the aggressions of Louis XIV. The treaty between Charles II and Louis XIV to which Sophie refers was the Treaty of Dover. About it one source says:

In 1670 Charles II and Louis XIV signed the Treaty of Dover. In the treaty Louis XIV agreed to give Charles a yearly pension. A further sum of money would be paid once Charles announced to the English people that he had joined the Catholic church. Louis XIV also promised to send Charles 6,000 French soldiers if the English people rebelled against him. For his part, Charles agreed to help the French against the Dutch. He also promised to do what he could to stop the English Protestants from persecuting Catholics.

This treaty was kept secret from the English people while Charles tried to persuade Parliament to become more friendly towards the French government. Charles used some of the money to bribe certain members of Parliament. These MPs, who supported Charles' pro-Catholic policies, became known as Tories by their opponents in Parliament.

The Dutchess of Portsmouth was a French aristocrat who became the mistress of Charles II at about the time of the treaty leading to speculation that she was sent to lure Charles into alliance with Louis. The Wikipedia article on her says she "concealed great cleverness and a strong will under an appearance of languor and a rather childish beauty." It also says the French government rewarded her handsomely and the English roundly hated her:

The Dutchess of Portsmouth was a French aristocrat who became the mistress of Charles II at about the time of the treaty leading to speculation that she was sent to lure Charles into alliance with Louis. The Wikipedia article on her says she "concealed great cleverness and a strong will under an appearance of languor and a rather childish beauty." It also says the French government rewarded her handsomely and the English roundly hated her: The hatred openly avowed for her in England was due as much to her own activity in the interest of France as to her notorious rapacity. Nell Gwynne, another of Charles's mistresses, called her "Squintabella", and when mistaken for her, replied, "Pray good people be civil, I am the Protestant whore."An anonymous pamphlet exposed the secret treaty a few years later and Ralph Montagu had his career at Court end dramatically in 1678 when he revealed its existence to the House of Commons.{click image to enlarge}

Wikipedia gives some background on habeas corpus in connection with Kings Charles II and James II.

The "sheets of advice to his son" can be found in Selections from the Instructions of King James II and VII to his Son. As you can see from this extract, Hume remembered well what he read and Sophie what she heard. It's the section of the advice (in one enormous paragraph) warning of the treachery of mistresses ("beware of such cattle"):

What you ought to arm yourself most against are the sins of the flesh, princes and great men being more exposed to those temptations than others, especially if they enjoy peace and quiet. This vice carries its sting with it, as well as all others, and with more variety it has that which is common with the others, which is that one is never satisfied, and no sooner has one obtained one object, but that very often at the expense of one's health, estate, nay honour and reputation, one desires change, and exposes himself again to all the former inconveniences. Those [women] of the greatest quality are not excepted, for if they once let themselves go, and give themselves up to these unlawful and dangerous affections, they are more exposed to the censure of the world than others of a lower sphere ... and I never knew or heard of but one who did not one way or other deceive their gallant ... all the world knows how most of those fine ladies have behaved themselves, not only after their gallants had quitted them for others, but while their greatest favour lasted, by having intrigues with others and giving with one hand to their true inclination, what they got from their abused great man, who was the only person who did not perceive how he was abused, and if they did, were so bewitched and imposed on by their fair ladies, as not to break quite with them, nor use them as they deserved. Would but kings, princes and great men consider and take warning of these kind of dangerous women, they would sooner take a viper into their bosom, than one of these false and flattering creatures; ancient histories are full of dismal relations of what have happened to kings, great men, and whole nations, on the account of women; wars, desolation of countries, besides private murders and blood-shed as well as ruin of private families which latter we in our days have seen happen but too often. [N]o galley-slave is half so miserable as those bewitched men are, for they know what they have to trust to, that they cannot be worse than they are, and have some rest and quiet; but these have none at all, being exposed to all the inconveniences which flow from their own jealousy. ... I cannot forbear giving one instance, for when at a club of some of the mutinous and antimonarchical Lords and Commons, it was proposed by some to fall upon the mistresses, the Lord Mordant the father, said, By no means, let us rather erect statues for them, for were it not for them the King would not run into debt and then would have no need of us. ... [H]ad not the king your uncle [Charles II] had that weakness which crept in him insensibly and by degrees, he had been in all appearance a great and happy king, and had done great things for the glory of God and the good of his subjects; for he had courage, judgment, wit, and all qualities fit for a king. ... And to let you see how little real pleasure and satisfaction anyone has that lets themselves go to unlawful pleasures, I do assure you, that the king my brother was never two days together without having some sensible chagrin and displeasure, and, I say it knowingly, never without uneasiness occasioned by those women. It is not proper for his and their sakes to enter into particulars, or else I would do it exactly ... Beware of such kind of cattle; they never consider but themselves; do not believe them, let them say never so much to the contrary. Can one be so weak as to believe that they that have laid all conscience and shame aside, will be true to any, but will be carried away by inclination or interest. I speak but too knowingly in these matters, having had the misfortune to have been led away and blinded by such unlawful pleasures, for which I ask from the bottom of my soul God Almighty pardon.

The listeners around the table would have known that Lord Clarendon did not support James II in his last days, but rather joined with William III and Mary in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when James fled England and was deposed.

The Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie, was the grandson of James II.

The Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie, was the grandson of James II. Earl of Albemarle to Sir T. Robinson, August 21st, 1753. "It has been positively asserted to me by a person of some note, who is strongly attached to him, but dissatisfied with his conduct, that he, the Pretender's son, had actually been to England in great disguise as may be imagined, no longer ago than about three months; that he did not know how far he had gone, nor how long he had been there, but that he had staid till the time above mentioned, when word was brought him at Nottingham by one of his friends, that there was reason to apprehend that he was discovered or in the greatest danger of being so, and that he ought therefore to lose no time in leaving England, which he accordingly did directly. The person from whom I have this is as likely to have been informed of it as anybody of the party, and could have no particular reason to have imposed such a story upon me, which could serve no purpose." (Lansdowne House MSS. )Mrs. Walkinshaw was a young daughter of an aristocratic supporter of the Young Pretender. Will Springer says he took her as his mistress during the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 at a time when he was losing interest in the fight. The daughter that the diary mentions was Charlotte, Duchess of Albany. The Wikipedia article on her says that Mrs. Walkinshaw and Charlie separated with allegations that he abused her and it confirms that he treated his daughter well, even making her his personal heir.

Here is a citation for the biography in which extracts from Lady Shelburne's diary appear:

Author: Fitzmaurice, Edmond George Petty-Fitzmaurice, 1stTo find this book in a library, click here.

baron, 1846- [from old catalog]

Title: Life of William, earl of Shelburne, afterwards

first marquess of Lansdowne,

Edition: (2d and rev. ed.) ...

Published: London, Macmillan and co., limited., 1912.

Description: 2 v. fronts. (ports.) plates, maps (1 fold.) 23

cm.

LC Call No.: DA512.L3F5 1912

Here's a link to the first post on Lady Shelburne's diary.

No comments:

Post a Comment